January 10, 2024 — Last year [in 2023] I flew to Los Angeles to see a performance of Promises, the 2021 collaborative album between Floating Points, the London Symphony Orchestra, and Pharoah Sanders, the final piece the free and spiritual jazz saxophone colossus wrote and recorded before he died in 2022. Shabaka Hutchings would be playing Pharoah’s part, his final performance on the tenor sax before he’d rededicate his craft to the flute and similar wind instruments.

The concert was at the Hollywood Bowl, which I had never been to before. My friend Hillary took me out for a nice dinner at Musso’s beforehand, one of those Hollywood steakhouses that feel way more storied and lore-filled than their New York counterparts, even if the bucket-sized cocktails and brigade of decorated waiters seem the same. This is probably because Brad Pitt has been filmed there, twice, sitting at the same place in the bar, first in Oceans 11 next to George Clooney, and again years later in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, sitting next to Leonard DiCaprio. Which is to say, I don’t get to L.A. very much but, apparently, get a little yokel rosy glow thinking about being in the same place where Brad Pitt was once there twice.

The Hollywood Bowl was similarly incredible. I grew up going to Alpine Valley in Wisconsin, a dizzyingly steep amphitheater in the small town of East Troy, which is like the Hollywood Bowl of Wisconsin, except it’s famous for (off the top of my head) being the only U.S. venue to host the Pearl Jam 20 tour and sort of killing Stevie Ray Vaughan. The fact that Stevie Ray Vaughan died when his helicopter crashed into a “ski slope” in southeastern Wisconsin, coupled with the fact that, in 1967, Otis Redding died 20 miles west in a plane crash outside of Madison, always made me think that southeastern Wisconsin was more famous for killing musicians than making them.

I wanted to be a saxophonist growing up. Specifically a jazz saxophonist, but I also did well at Wisconsin’s more buttoned-up statewide Solo and Ensemble competition playing classical saxophone pieces, an oxymoron that any honest classical saxophonist will admit to—if you can find one. It’s fascinating what goes into a 4th grader’s decision to choose a band instrument. At my school, there were girl instruments (flute, clarinet, french horn) and boy instruments (trombone, baritone, percussion) and what seemed anecdotally like gender-fluid instruments (trumpet, saxophone) which self-sorted the majority of kids. My best guess as to why I picked tenor saxophone was because something in the culture of the ’90s told me it was cool, some mix of catching Lenny Picket on SNL, Lisa Simpson, seeing a Snoopy shirt where he’s playing the saxophone, and hearing the Champs’ “Tequila” in Sandlot.

Practicing the saxophone was not something I enjoyed, but I did enough to be really good for a high schooler, which is different than enough to be really good on a professional or creatively interesting level. I practiced a few hours a day, transcribed solos (Hank Mobley’s solo on Art Blakey’s “Moanin’” was my big project), did my scales, and stumbled through the Bb Charlie Parker Omnibook. When I heard how much my music major friend Bobbi was practicing her freshman year at school (4-5 hours a day if not more) I knew I did not then have the required focus or fortitude to hang in a small room by myself over hanging out with other people.

December 30, 2024 – I was late writing my annual essay last year—c.f. the dateline above. I was about to plow through and finish writing about how seeing the Floating Points’ Hollywood Bowl Promises show—affectionally referred to by me and my friend Hannah as the FloPoHoBoProSho—reconsecrated my love of jazz, how my chilly and complicated and stultifying relationship to music and writing was undergoing a great thaw. Steam emanated from my entire body like I had just finished a hard run on a cold morning. I had found this backchannel into what I originally loved about sound and playing, communication and possibility—this music was about reaching for something outside of yourself. Not accretion but ascension. Not about status but the stochastic. A higher power, touching infinity. I was reinvigorated and excited to follow this path and everything it no doubt would compel me to want to write about, because my spirit was fully reborn inside of me.

And then the layoffs. I had been laid off before, at CBS. I had been fired before, from VICE. I had shown up to work only to realize that job suddenly didn’t exist anymore—twice—once while doing my radio show for Red Bull Music Academy and earlier in my life at Papa John’s after the franchise owner was finally arrested for his fifth DUI. But this was the first time in my life I was leftover, which carried with it a surreal kind of survivor’s guilt that reacted chaotically with my inborn work ethic and years of running the reviews section. For obvious reasons, I won’t talk much about the Pitchfork layoffs here, but maybe much later in life when all this is in the rearview.

As it relates to this, the layoffs in January meant one thing: I was not about to finish writing a blog about how ambient jazz saved my life. Whatever thaw I was experiencing then in 2023, was suddenly and cartoonishly re-encased in ice. By the summer, I pulled up this document again to see if maybe I could recapture that feeling I was trying to express, but it didn’t feel right—and more honestly, I just didn’t want to do it.

But here I am, almost a year later, to wrap up my thoughts, feelings, and impressions about what I heard this year. While rediscovering my love of jazz was the start of my relearning how to love music, a second thing happened this year that caused me to change how I hear music: I really started DJing this year.

I relayed this thought in passing to an outstanding DJ and producer and musician backstage one night at this year’s Unsound Festival in Krakow, Poland. “I really started DJing this year,” I said in the excited manner of someone who had just discovered Goodfellas or food. Beside us, a mutual friend noted how good of a DJ this artist was as if to hint to me that they had indeed eaten food and seen Goodfellas many times. I made sure to recalibrate my approach. “I know everyone’s a DJ, and this is going to sound corny,” I said, “but it has really changed how I listen to music. And I’m in that bright glow of discovery right now where everything feels new and unselfconscious, and this thing is moving purely from impulse to impulse. It is like hearing music for the first time again.”

In a world-historic show of grace and excitement, they agreed with me and wished me well on my journey. By playing other peoples’ songs at slightly different tempos in an order of my choosing, I have found a tool that has let me approach music from a new valance, one that is far less intellectual than I am used to. It’s a different circuitry than everything I had been wired to think about when it comes to writing. What does Patrice Rushen have to say to Happy Mondays? How does a TB-303 acid bassline work with an ARP bassline? What does this crowd like? What sounds absolutely sick through a great sound system? Surely, this is what Larry Levan and Kool Herc and Jeff Mills were thinking about: How can I play records to unshackle my brain from the strictures of what it means to be an editor and music critic?

I love how a DJ can show you what they’re feeling, tell you a story, and be a historian and a critic without saying a word. Unfortunately, my lot in life is to attempt to put into words what is otherwise difficult to describe. This has been easiest for music with which I share some common literary ground: surrealist poetry, formalist rhyme schemes, classical romanticism, self-mythology, self-effacement, world-building, humor, all manners of guitar solos. I wrote reviews of two of my favorite records this year—MJ Lenderman’s Manning Fireworks and Jessica Pratt’s Here in the Pitch. These records are so familiar to me that they might as well have been hatched from my spinal column. The second I heard them, I could see their full cosmology written in the sky, how it connected to my life, my music, my reading, my emotions, my specific view of the world.

There’s an idea that I toss around in my head often—bastardized long ago from Dave Hickey’s dizzyingly good memoir Air Guitar—that critics write about art in the hopes of giving credence to themselves. That the books, movies, art, and music that critics love are actually just pieces of themselves, and that praising art is just a way to validate a critic’s lived experience. In every review, this is true and goes unspoken. And since earned authority and unimpeachable rhetoric come from years of experience, a critic, in a sense, is not just praising an artist, but tacitly praising what they know about themselves. It could be argued that subconsciously, all criticism is about wanting to see yourself projected a little larger in the light of someone else. (This is what I think The Substance should have been about.)

Of course that’s not all criticism or writing is, but it’s its dark Jungian shadow. You’re having a conversation with art that you’re actually having with yourself. But that conversation is best when you believe you have something in common with the artist. I will always couch morsels of honesty in broad jokes because I think that way people will believe me; yes, I like to take a little edible and put on airy records that let me wonder about time and love and the cosmos like I’m a couch-bound Christopher Nolan. But I believe my job as a writer and critic is not to simply reify all that I already know about myself to validate my path up until now, but to constantly be trying to start new conversations, to say “I’m starting to DJ,” be flushed red by how corny that is and persevere through the flailing, fledgling stages of learning how to talk to someone else.

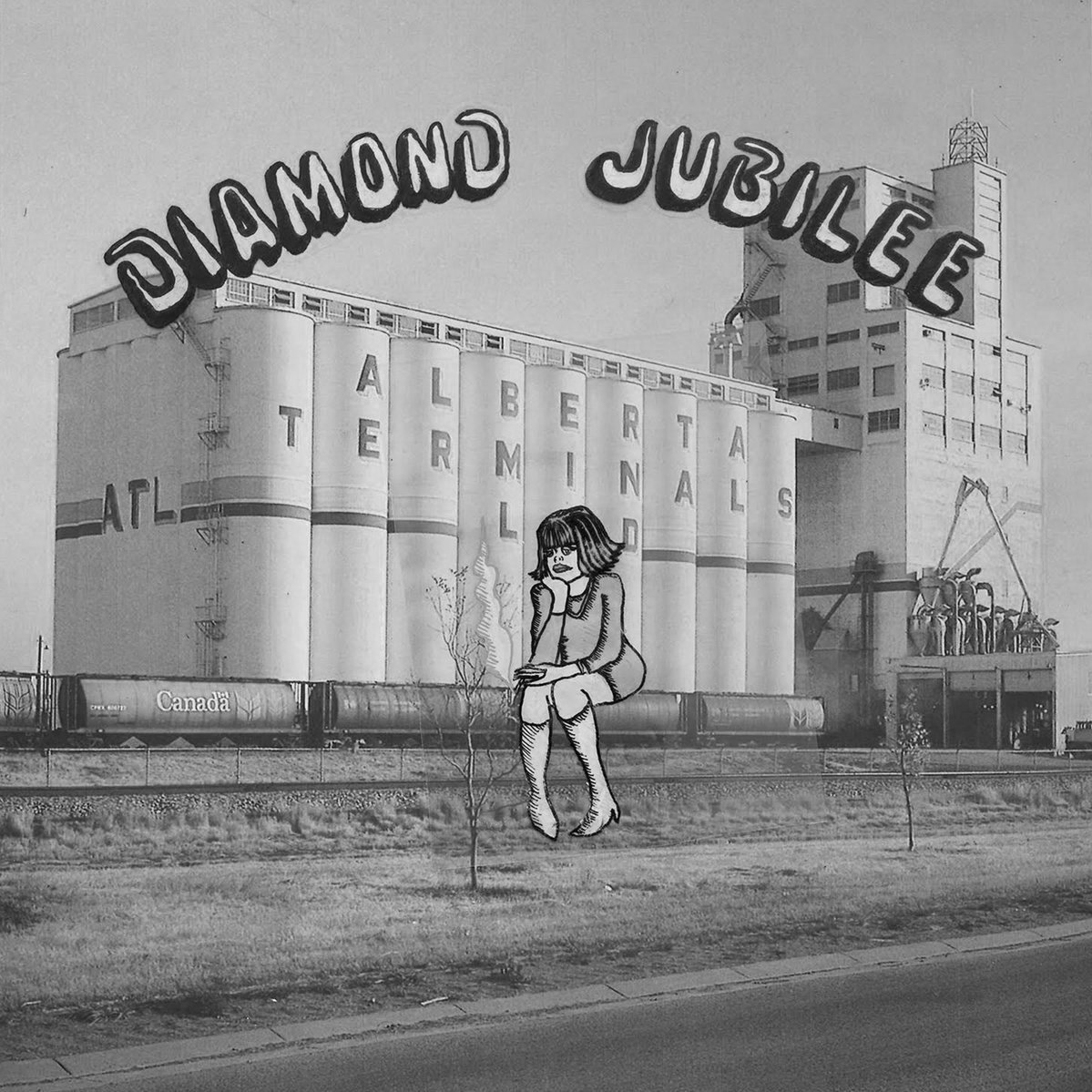

What I loved about Cindy Lee’s Diamond Jubilee was not that it immediately spoke to me, but that it was clearly speaking to someone else. Many, many other people, here and gone, real and imagined. It is art in conversation—cooing, howling, strutting, gesticulating, prowling, twirling one shoulder, swaying, crying, crying, and crying—with the ghosts of Americana and, uh, Albertacana. It is a dialogue about fidelity and gender, about pop and the underground, about distro and marketing, about streaming and royalties. I didn’t need to say that I see myself in Patrick Flegel’s world, but that Cindy Lee’s musical biome was so rich and fertile and alive that it felt self-negating. It existed so toweringly, so singularly on its own terms that I didn’t have to exist at all. Good music makes me feel seen, great music makes me feel obliterated. Wiped off the map.

Like Seneca before me, I’ve moved to the suburbs. There, I’ve started DJing a monthly party at a small bar called the Copperhead Club in Peekskill, New York, with my buddy Joey. He’s very good and I learn a lot from him. For four or five hours we go B2B, and while I love the ascetic, fastidious nature of planning out a long solo set, DJing alongside someone else is so creatively fulfilling. It is like improv that absolutely no one cares about—which is the truest form of improv—and understanding how to have that conversation and getting better at having that conversation is so enriching to my relationship with music. We play goofy, we go deep, we go soft, we go pop. In his heart, he’s a big deep house guy, and I’m more of an Italo disco guy, but we find ways to overlap (basically it’s François K.’s “Hypnodelic”). Everyone who works at the bar is a perfect gem, the regulars and stoppers-by dance a lot—I look forward to it every month because it’s a small community that really supports each other. We close every night dancing with the late-night crew to Double Exposure’s “My Love Is Free,” which makes me feel lighter than air.

I’ve also made a few mixes this year, most recently—and the one that sounds the best—is my “Jazz Not Jazz” mix, which collects a small amount of songs from 2024 that have oblique approaches to the timbres and sonics and chords of jazz without really adhering to the traditional form at all. I love the expression of jazz seeping into indie rock—Geordie Greep and Fievel Is Glauque—and improvised psychedelic music—Jeff Parker, BASIC—and of course new age and ambient—Rafael Toral, Carlos Niño, and maybe just Los Angeles writ large. You have to donate a bit of yourself to the voicings of chords that stretch back almost a century, invoke a tradition, and unselfconsciously invite the past into your music as opposed to self-consciously blotting it out.

I’ve also done my 6th annual “Best Little Moments” spreadsheet. Admittedly the UX of a spreadsheet is quite poor, but—and this is the first time I’ve ever typed this—with the help of prompting artificial intelligence for 20 minutes, I’ve been able to turn my Best Little Moments into a much more friendly webpage, which you can click on here or at that button below. I’ll update the other ones soon!

So much of this year has been spent squirreling away ideas for a much larger writing project that I am working on, so a lot of these threads I’m pulling on here will one day be knitted into something larger. But what I will say is the most my brain was lit up this year was at Unsound Festival in Poland. Similar to Nashville’s Big Ears, Utrecht’s Le Guess Who, and the dearly departed rotating RBMA Festival—it was a meticulously curated experimental music festival that relied on you trusting the programming from soup to nuts. But giving yourself over to the abyss of the unknown reminded me what I loved so much about curation in the first place.

I was in a room of 300 people watching the noise band MOPCUT, a band that makes Still House Plants sound like the Monkees. I stood there watching a rare Yellow Swans set and a 72-year-old Keiji Haino and was obliterated, negated, rendered small and silent among the noise lords and the Eastern European techno teens in druidic hoods and long leather dusters. Immersed in this art and body and noise music created a total sensory, intellectual, and aesthetic experience—all I could ask for as a vessel that is either full of holes or bottomless. I came in blind, under the auspices of the festival, the Polish government, as a +1 to veteran panelist and performer Phil Sherburne, who was there to moderate a chat with Bill Callahan. I left with a notebook full of ideas about sound, silence, creation, and destruction.

One night, after an exceedingly rich Polish dinner consisting of rye soup and goulash with Phil, Andy, and Bill, we crammed into an Uber to go see the Sinfonietta Cracovia perform a suite of Mica Levi compositions. Bill is a taciturn man, but incredibly kind and attentive. We talked about the mind-body relationship to pain (of which my wife is a huge proponent) and the kinds of music his son likes. It was a lovely chat filled with many unstrained periods of silence.

After about 20 minutes, we arrive at the venue. I get out of the car, pat my pockets, and realize I don’t have my phone. Bill crawls out behind me, holding my phone in his hand. “Thanks,” I said.

He said, “All I get is a thanks? I just saved your life.”

1. Cindy Lee - Diamond Jubilee

2. Jessica Pratt - Here in the Pitch

3. Jeff Parker / ETA IVtet - The Way Out of Easy

4. MJ Lenderman - Manning Fireworks

5. Waxahatchee - Tigers Blood

6. Nala Sinephro - Endlessness

7. Rafael Toral - Spectral Evolution

8. Geordie Greep - The New Sound

9. Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru - Souvenirs

10. Mount Eerie - Night Palace

11. Ka - The Thief Next to Jesus

12. Milan W. - Leave Another Day

13. Astrid Sonne - Great Doubt

14. SML - Small Medium Large

15. Mk.gee - Two Star & the Dream Police

16. Total Blue - Total Blue

17. Nídia & Valentina - Estradas

18. Charli xcx - Brat

19. Fievel Is Glauque - Rong Weicknes

20. Adrianne Lenker - Bright Future

21. Contrahouse - Contrahouse

22. Peel Dream Magazine - Rose Main Reading Room

23. Blood Incantation - Absolute Elsewhere

24. Being Dead: EELS

25. Joseph Shabason & Ben Gunning - Ample Habitat

26. Ethnic Heritage Ensemble - Open Me, A Higher Consciousness of Sound and Spirit

27. Another Taste - Another Taste