Jeremy Larson’s favorite albums of 2024, best little moments of 2024, and a yearly essay about where it’s at.

Read MoreFavorite Albums of 2023

Jeremy D. Larson’s favorite albums of 2023, plus a link to “Best Little Moments”

Read MoreFavorite Albums of 2022

Before I get into this, I want to reset the table, align the flatware, and make clear why I’m writing a long essay. I want to give you a better reason to read this. For seven years, I’ve been doing these year-end prologues to accompany my list of favorite albums. (You can find them at the bottom of this page.) Originally I was just writing little blurbs for each one, but that slowly expanded into protracted personal essays and grand unified theories of how the exact events of the calendar year led me almost scientifically to arrive at my favorite two dozen or so albums. These essays have helped me give shape to something that is increasingly difficult to measure: my taste in music.

My job demands I think about taste constantly, and squaring my taste with that of my colleagues and our readers is—as I see it in my head—an extraordinarily tense ballet. Taste is about many things, though it is arguably about everything: status, social capital, identity, class, income, environment, family, education, desire, fear. The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s rigorous but increasingly dated book Distinction is probably the leading, 613-page definition of “taste.” Bourdieu spends a lot of time theorizing about how class plays an important part in developing taste, that—among mid-century Parisians at least—there’s a pervasive working-class aversion to, say, avant-garde theatre or non-figurative painting because it’s unclear what these artworks are supposed to signify. Kitsch and pop art feel good immediately, whereas experimental art breaks down the conventions of what makes things enjoyable. If you don’t have a working definition of what makes pop and kitsch enjoyable, Bourdieu posits, it’s near impossible to understand a dissonant, arhythmic, asocial work that subverts it.

I’m not a sociologist, but I do play one in real life. And so I believe—said with a swirling of my hand and a gentle pull from a vape pen—that most negative responses to art are rooted in fear. Fear of social acceptance, fear of misunderstanding, fear of ridicule, fear of identity betrayal, fear of identity loyalty, fear of self, fear of youth, fear of death. Among the many pull quotes in Bourdieu’s book is this bit about dichotomies, about how taste is “first and foremost [about] distastes, disgust provoked by horror or visceral intolerance of the tastes of others.” This feels holistically connected to Hua Hsu’s riveting 2022 memoir Stay True, which acts as a personal case study in taste and friendship, Derridean différance and covalent bonds, Fugazi and Pearl Jam. As Hua recalls his turn-of-the-century friendship with a college friend named Ken, he feels at odds with this guy whose structureless, pop-kitsch consumerist taste in music and fashion doesn’t comport with his own rigid, leftist, anti-capitalist, “authentic” taste. Hua, the aesthete publisher of a zine, liked Pavement; Ken, a frat boy who wore his hat backward, liked Dave Matthews Band.

By the end of Stay True, you get the sense that instead of this being about how a collegiate odd couple came to understand each other by trading a burned CD of Under the Table and Dreaming for a cassette tape of Slanted and Enchanted, it’s that you perhaps already contain that which isn’t you. That when you love someone (a friend, a partner, a brother) with different taste, you realize, in the Derridean sense, that all that disgust and horror would not exist without its concomitant love and curiosity. It’s about the volatility of opposites, the ability to see yourself in someone else, subsuming them, becoming who they are. Near the end of the book, when Hua finds an auto-fictive movie script Ken had been working on, he sees a rendering of his persona through Ken’s eyes on the page. It’s the moment the molecules of two insoluble liquids go through some kind of alchemical reaction and become a distinct whole.

It’s in this vein that I believe true taste—at the most atomic level—is about friendship. Oh brother, how sentimental. How mawkish. How kitsch! Well, you see, over the past year, I’ve been keeping a playlist called COMMUNICATIVE IN 2022, where I compile a list of old songs that I have, in some way or another, found a new connection to. Some were added from spending time editing Sunday Reviews and reading about the writer’s relationship to it (Bonnie Raitt’s “Nick of Time”; Terry Callier’s “Golden Circle”). Some I found a new love for after hearing it used in a movie or TV sync (Joe McPhee’s song featured in the “defiant jazz” scene in Severance, for one).

But most of the playlist consists of recommendations from other people. Each song is a memory I recall vividly: Chatting on Slack with Sam about Karate and then later, Gary Stewart, or DMing with Schnipper about A.C. Marias, one of many bands I discovered on his indispensable Deep Voices playlist, or in a group chat with Mark about how much he thought Thomas Brinkmann’s “On Edge” reminded him of 100 Gecs’ “Doritos & Fritos,” or how someone at work made fun of me for never having heard Camp Lo “Luchini AKA This Is It” before our ’90s list, or Anna talking about how she really loved early Ezra Furman, or how Bill knows I like noodly stoner stuff on summer afternoons and sent over Jonathan Wilson’s “Desert Raven.”

Is this taste? This inscrutable playlist whose only throughline is a mysterious autobiographical appendix that I’m only cryptically sharing in an abridged form? It’s certainly more tangible to me than imaginary guesses at music that connotes some kind of social rank, or over-torqued posts or essays about music’s political efficacy, or wild swings at what, actually, the indie sleaze revival is subverting. It was easier two decades ago to say that you hated Dave Matthews Band because they stood for everything Pavement was against. It was easier for me in the retrograde, gender-conforming days in my rural high school to not like Britney Spears because she was commercial pop music for girls and instead spend my time listening to Dream Theater and Metallica, boy music with more notes. In the super-saturated, non-linear, algorithm-driven, personality-based music ecosystem that exists today, it’s increasingly difficult for me, in good faith, to like something because it is in opposition to something else. There are a handful of albums this year that still thrillingly kicked and thrashed from a defensive stance (Soul Glo, Special Interest), I still find myself in the thrall of nu-prog as a blunt tool against the tyranny of common time (Fievel is Glauque, Black Midi), and I will forever be in awe of the simple idea that a few people can sit one room and create, over the course of 60 minutes, music that serves a higher spiritual force (Jeff Parker’s Mondays at the Enfield Tennis Academy).

But in reality, because of social media and oversaturation, there is very little action or reaction in music. Billboard hits are either preordained by the money afforded to major label artists or bizarrely capricious. The latter songs bubble up from TikTok into an exponential viral snowball, fuelled by users making a safe bet by creating content using the most popular TikTok snippet there is, thereby having a greater chance people will view their own content. And on and on it goes. Songs are made popular by the individual desire to become popular.

Both of these modalities for chart success seem to exist in the vacuum of the individual song and the personality of the creator, not part of some broader musical era connected by a sound, theme, or trend. So what stands in opposition to this? Who will don the “I Hate Pink Floyd” shirt that sparks a movement that shifts the pendulum away from social-pop hits to give dimension to a scene whose admiration might connote good taste? I had hope for hyperpop, but that is quickly waning. I fear that the methods of Oneohtrix Point Never—my erstwhile sage of futuristic composition through recontextualizing the past—are now becoming a homogenized and common trope with other pop producers. I fear generative A.I. will probably take over large sectors of the music business. So what is this year’s “grand unified theory” of what music should be about going forward, something that can drive taste other than the friends we made along the way? I have one very small idea that I hope to expand into a larger thesis.

There’s a moment when Exuma’s 1970 song “Exuma, the Obeah Man” came on in the third act of Jordan Peele’s Nope. I started levitating. What is this, who is this, I am sure this is the greatest song I have ever heard. Exuma—I found out later—was a Bahamian-born singer who worked in New York and recorded a few records in the ’70s for a major label, when there was a small market for gravelly, leftfield psychedelic rock in the vein of Dr. John or Captain Beefheart. He never really took off in the mainstream, and while the artist born Tony Mackey kept writing and performing up until his death in 1997, his music remained mostly sought after by crate-diggers. The song Peele carefully selected for Nope is Exuma’s de facto anthem, an Afro-spiritual celebration full of stomps, clanks, whistles, and ribbits. It is a dark night on the beach, and there’s a fire blazing at its center.

I don’t even know if Exuma in Nope was my favorite movie-music moment of the year: It’s up there with the Clash’s dub version of “Armagideon Time” that appears (somewhat obviously in retrospect) in James Gray’s Armageddon Time or Lydia Tár and her wife dancing to Count Basie and talking about slowing the heart rate down and nitpicking the actual bpm of the song. But Nope is my No. 1 movie of the year, and my favorite of all of Peele’s movies thus far. It is not just for the needle drops (like when Kiki Palmer grabs a Congos record off the shelf) and the diabolically high concentration of band shirts (Earth, Wipers, Jesus Lizard, RATM) that are clearly playing to, well, geeks like me in the audience. But it is a movie full of big ideas that come from little unforgettable moments. A bloody shoe suspended in gravity suggests something OJ coins as a “bad miracle”; a Bahamian jockey in the first moving picture suggests a desire to give agency to lost figures in entertainment; a billowing, blood-sucking, polyester alien suggests the inability to capture a spectacle without it taking something from you in return.

Peele and critics refer to his movies as “social thrillers,” but Nope is also another type of genre, the latest in a long line of movies about making movies. People like me love these movies because, guess what, we love movies. From Singin’ in the Rain to 8 1/2 to Mulholland Drive to just about every Tarantino film, studios will seemingly greenlight any film loosely about the art, craft, or business of filmmaking. You like movies? Wait until you see a movie about ’em! Of course, what Peele has to say about movies and Hollywood’s history is far less rose-tinted and tinsel-strewn than his contemporaries. It’s a sharp stick in the camera’s eye.

It follows that I also love music about music. My favorite example is funk, whose songs are chiefly concerned about how good funk music sounds, the music you are presently listening to. In the ’70s and ’80s, rock bands built entire careers about how their rock songs rock, taking on a kind of self-appointed ombudsman role whose tautology was widely overlooked by their audience. Country songs remain very much about country songs, and are probably the most direct analog to movies about movies, given the propensity for both to be either nostalgically effective or charmingly clever. Rap is in constant conversation with itself, though rarely is this as openly acknowledged as it once was, partly because of the genre’s propensity to quickly evolve and eat the father, and partly because rap’s conversation with its past through samples has been diluted from an artform that built a new network of Black art to something far more Xeroxed and insignificant in recent years.

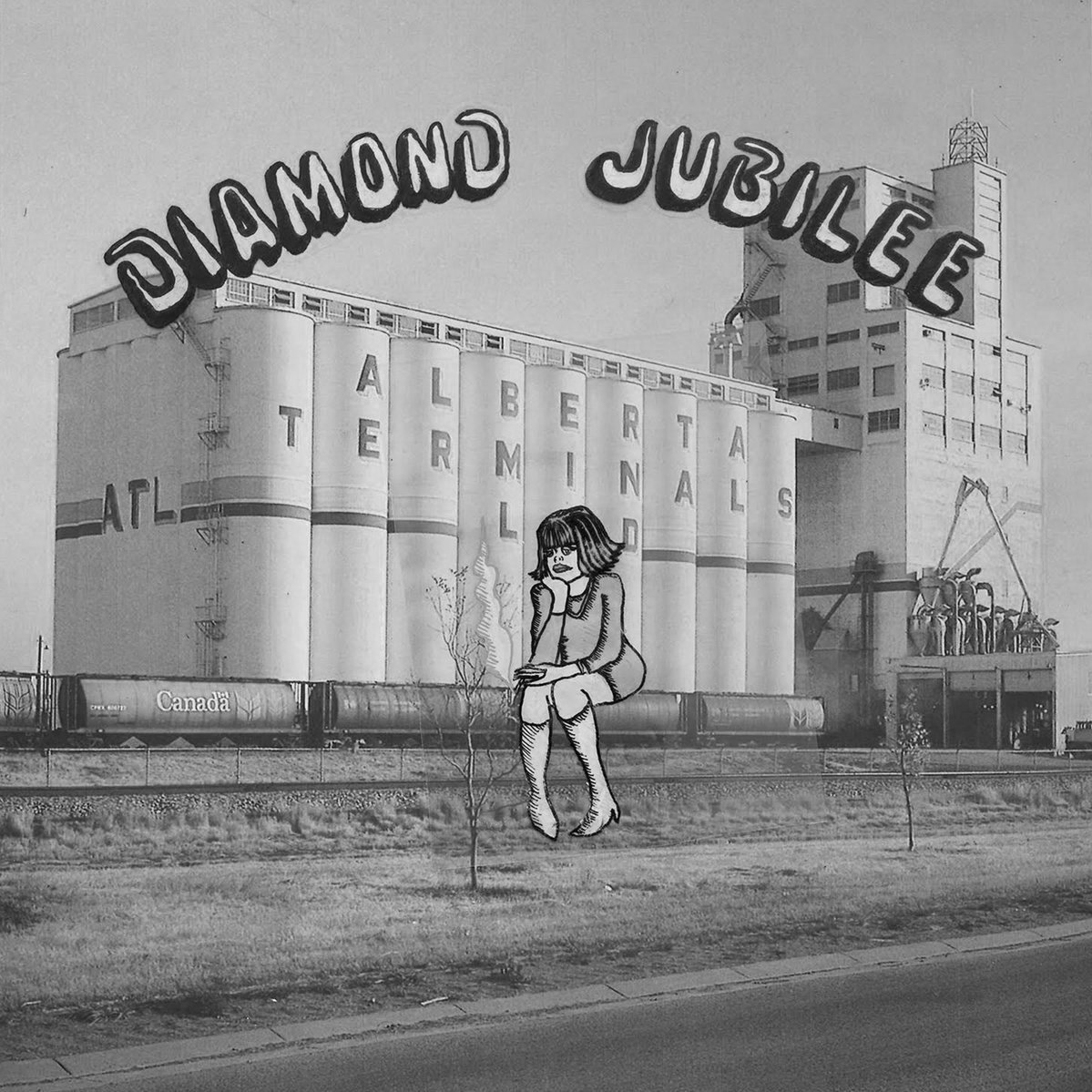

This was the year that I was drawn to music about music. This idea is about both examining its past, lifting up old voices, and ensuring its survival. It’s what I enjoyed so much about Wednesday’s eclectic covers album. It’s why I was fascinated with Father John Misty’s singular retreat to the golden age of bandstand jazz. It’s why I connected to Beyoncé’s it’s-not-said-enough-how-weird-this-album-is Renaissance. And it’s what I loved about Alvvays’ Blue Rev, an album in thrall to little moments from music’s past and putting forth a bigger, singular idea about the sound of pop and rock music. I could annotate every meticulous detail of Blue Rev and still feel like there is more that I’m missing. The oblique, romantic, cinematic lyrics don’t make me wonder what Molly Rankin is feeling about something, or who she is talking about, or why. Instead, they reconnect to old ideas of mystery and obfuscation. When I am listening to these albums, I’m not just listening to music, I’m listening to more music.

I could argue that these things make Blue Rev gently in opposition to the mainstream, but I would hardly suggest that this is some kind of catalyst for radical change. But it also feels like a friend saying, “You know what I think you would like? A pop album that sounds amazing on vinyl with key changes, bridges, guitar solos, and a song that makes direct reference to Belinda Carlisle’s ‘Heaven Is a Place on Earth.’” That’s the true heart of criticism, casting about for a center in hopes to find yourself already there. You discover a song that is so who you are that you have no choice but to try and tell the world so that they can add you to their playlist.

1. Alvvays - Blue Rev

2. Jeff Parker - Mondays at the Enfield Tennis Academy

3. Special Interest - Endure

4. Father John Misty - Chloë and the Next 20th Century

5. Beyoncé - Renaissance

6. Jockstrap - I Love You Jennifer B

7. MJ Lenderman - Boat Songs

8. Soul Glo - Diaspora Problems

9. Grace Ives - Janky Star

10. Beth Orton - Weather Alive

11. Gilla Band - Most Normal

12. Big Thief - Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe You

13. Lucrecia Dalt - ¡Ay!

14. Makaya McCraven - In These Times

15. Yaya Bey - Remember Your North Star

16. Huerco S. - Plonk

17. Destroyer - Labyrinthitis

18. The Weeknd - Dawn FM

19. Panda Bear / Sonic Boom - Reset

20. Fievel is Glauque - Flaming Swords

21. Rosalía - MOTOMAMI

22. Two Shell - Icons EP

23. My Idea - CRY MFER

24. Sofie Birch - Holotropica

25. Anetloper - Pink Dolphins

Favorite Albums of 2021

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2020

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2019

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2018

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2017

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2016

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2015

Favorite Albums of 2021

“And somehow the music we all grew up listening to doesn’t relate to our adult reality and our new dreams. The music we grew up with doesn't speak for us in the new era we’re now going through. Our childhood dreams have become the basis for our adult fantasies. And now, simply, we all grew up to be something new.”

This is from Oneohtrix Point Never’s remarkable album Magic Oneohtrix Point Never, a bit of dialogue from a radio station changing formats midstream, which he adds in as interludes throughout. (There is an archive of them, I recommend it.) The album came out in 2020, but I listened to it a lot at the beginning of last year, as Daniel Lopatin’s music usually takes a while to gain a foothold in my brain, especially with a listening schedule as cluttered as mine.

There’s no better thinker about the musical past than Lopatin. He’s so wise about its allure, interpretation, and revision on every album he’s made and every interview he’s done, including a long section in Simon Reynolds’ Retromania, and on Lopatin’s defunct Tumblr where he coined the indispensable phrase “timbral fascism.” It is a phrase I think of every time I hear a slap bass or a Farlight synth or a 7-string guitar.

Just as I can hear Loptain wrestle with the past in his music, I find myself fighting way too much with the past as it informs my criticism. Increasingly I think this may be a faulty or insignificant or uninteresting way to think critically about music.

Maybe we should do away with the past. Not literally—like the bad guys (?) in Christopher Nolan’s Tenet—but the concept of it when it comes to music criticism. The idea that art evolves in a linear fashion, or even in retro- or revision cycles, will soon be (if it isn’t already) outmoded. Culture cycles so fast that it’s now adopted the illusory “wagon-wheel effect”—though it is spinning, it appears not to move at all. The past is static, a telescoped digital archive, one incomprehensible pool from which to siphon. A flat circle, that’s right.

Here’s a keyhole into my personality: I don’t play video games, but I reserve that adolescent space in my brain for an unconditional love for every Christopher Nolan movie. I think it’s an even trade-off.

In a year when the word “nostalgia” has made a remarkable evolutionary leap to mean “literally any time before this exact moment,” there is just so much hand-wringing about the value of the past, who has agency over it, who can speak for the primacy of its existence, what is gained and what is lost from invoking it, and what it is even worth. Just now on Twitter I saw someone discover “momcore” artist Liz Phair to the chagrin of a handful of people; a famous TikTok guy has a series called “indie songs from the 2000s that still slap” volumes 1 through 21—very few of them are from independent artists, and only some of them still slap.

Whenever you observe someone younger than you offer a unique opinion about a piece of culture you witnessed firsthand, please select one option from the to the four-quadrant Billie Eilish Doesn’t Know Who Van Halen Is Opinion Matrix: I respect this and don’t need to say anything about it; I don’t respect this and need to say something about it; I don’t respect this but don’t need to say anything about it; I respect this but I need to say something about it.

As life in the Anthropocene tips into a gradual decline brought on by the irreversible effects of climate crisis, the past becomes a highly valuable commodity in criticism because the future gets more volatile by the second. Those of us with a lot of time in the bank account sit comfortably on hundreds of thousands of pre-pandemic hours, while younger, more time-poor people wonder every day what kind of past they will actually inherit—what will their past be worth? This is an analog to the depletion of the social security trust fund in 2033, maybe.

It’s not just the value of pre-pandemic hours—though perhaps that will be an important bookmark in the future—but any hour where you maybe simply got through the day. I have almost 37 years’ worth of those now. Every time I speak to someone with fewer, I sense there is some kind of age-based intersectionality politics going on, that I have had the privilege of experiencing life, and therefore I should demure to someone who doesn’t have all that time saved up in the bank. Surely—surely—I’m projecting this, but it’s a fear nonetheless.

They covet my nest egg of glory days!

This idea is partly explored in HBO’s adaptation of Station Eleven—a very earnest and moving show pitched emotionally and aesthetically somewhere between The Leftovers and Watchmen. It addresses both my thought experiment about destroying the past and my once glowing artiste persona that believed Shakespeare could really, you know, fucking change the world. It’s very precious about the power of art, which is something I have silenced over the past 8-10 years as my brain grew an enormous teratoma called “online music critic” that is powered faintly by a mostly dormant “creative spirit.” I really want to begin to reverse that relationship this year, you know, like the woman in James Wan’s 2020 horror film Malignant.

Anyone can hear the past on a playlist, but what if you lived it as it was happening? Can someone else have a better claim to the experience of that music? In the end, does this comes down to what it always comes down to in music: Drugs?

I still tense up every time I watch a scene in a television show where a group of people walk into a crowded bar or restaurant, maskless, as if they just stepped into the big cat exhibit at the zoo. Even two characters just coming in for an unselfconscious hug. I had so many years of not having to worry about any of that, and the generation below me and below them will have had so few. Will they hold that against us? Should they? I wonder if this will create a new wave of criticism—an epochal split—that functions with a big chip on its shoulder especially as it pertains to the more linear past, the pandemic, climate crisis, failing democratic systems, or Frank Ocean becoming a weird jeweler instead of ever putting out another album, whatever it may be.

PinkPanthress liberally cribbed Sweet Female Attitude’s 2000 UK garage hit “Flowers” for her great breakout single “Pain.” It was a fascinating moment for me, someone unfamiliar with “Flowers” until I heard “Pain.” Usually, I’m pretty good at picking up on samples—my first critical thought about any new piece of music is usually hmm sounds like… which, again, I am now interrogating—but “Flowers” was in my blindspot. I have no nostalgia for “Flowers” and so I just really loved “Pain” without any hangups about my knowledge and experience of the past.

I wish this is how I could experience all new music.

This summer, I broke my clavicle about five miles into the bike leg of an Olympic triathlon, which is a 1500m swim, then a 25 mile bike, then a 6.2 mile run. I took a sharp left turn going about 20 miles per hour, caught some loose gravel in the middle of the road, and my bike slide out from under me. My shoulder took the entire weight of my fall and I went sliding on my left arm and left leg about twenty feet across the asphalt and into the ditch. People passed me, Malcolm Gladwell’s relay team passed me, and just sort of looked as if they wanted to help but were helpless to stop. I was angry, screaming goddammit! and stomping around, knowing my first ever triathlon race was probably in the trash, entirely unaware of the crack in my collarbone and the tiny to not-so-tiny pieces of road that had dug themselves into the flesh of my arm and leg.

Bloody, sweaty, dazed, hastily gauzed up by a nearby sheriff’s deputy, I decided to get back on the bike and finish the next 20 miles of the leg. Then I finished the run. Then I went to a nearby Urgent Care. I would have personally beat Malcolm Gladwell and all of his entire relay team had I not crashed, I later thought as I sat in the car with my arm in the sling in which I would spend the next six weeks.

Endurance is a genre of sport I have pathologically thrown myself into over the past few years (marathons, triathlons; I’ll be doing a Half Ironman (1.2 mile swim, 56 mile bike, 13.1 mile run) in Roanoke this summer) and I’m still very in my head about why I do it. I suppose I like tangible, measurable progress in my life because it otherwise has so much subjective growth and validation.

The career ladder of a writer is…squiggly, and if you measure your place on it based on social media or money or career, you will be sorely disappointed by those metrics as it pertains to the actual art and craft of writing—something you can only guess that you are getting better at year by year. At best, you are writing something that you are at this very moment proud of. At worst, you don’t know what you’re writing because you hate who you are at this very moment.

I wonder if the decision to endure competitively says something inherently about your spirit, that it is especially fortified. When I do a 5k time trial on the track or a functional threshold power test on my bike or finish a triathlon with a broken collarbone, I enter what a lot of athletes call the “pain cave.” I seek it out because it is among the most stimulating events in a largely inert world, a high that is so difficult to achieve, that every time it happens it destroys you for a day or two, or even a week. Maybe it’s an exorcism of past emotional pain and suffering. Or maybe it is a blueprint of the pain and suffering that I haven’t experienced yet. Maybe it is, as my buddy Bill says, just an exercise competition.

I listened to a lot of Turnstile while I was running fast this year. A lot of the Armed (“All futures, destruction” is the motto.) My most played song while running or biking was “Assisted Harakiri” by the emo band Home Is Where, not entirely but chiefly because the tempo is about 190bpm, the pace that really forces me to lift up my knees at a clip and keep pushing through difficult speed workouts. I continued to miss the experience of hearing a song live, in a club, from a car—so these moments I spent with my running playlist and its psycho-physical connection is the strongest bond I made with music. I wonder whether the release of endorphins from running is similar to the release of dopamine from weed or MDMA when it comes to how you hear music, how it means something more to you because of it.

Hush-hush, keep it down now: For two years some of my favorite albums featured people talking quietly into my ear. Last year it was the Microphones’ autobiographical memory-play, this year it was Dry Cleaning’s debut album. Florence Shaw’s droll and surreal recitatives arrived when cabin fever was at its peak; when my brain was sanded down and buffed smooth as a bowling ball. Cometh the time, cometh the album. Her fascination with words, phrases intonation, inflection inspired such an equal fascination with me: hippo, dick, Mighty Oaks, Elmo costume, useless long leg, reverse platform shoes, Sherlock Holmes’ Museum of Breakups.

I started therapy this year because I told my therapist I have too much clutter in my brain. There are too many knots. The Christmas lights, they all work they’re just in a big ball in a box in the basement. I just need them untangled. Psychologically constipated.

I felt Dry Cleaning was this codex to this feeling not just in my brain but maybe in the world. Drawing meaning from nothing, just seeing two random nouns together for the first time and projecting an entire worldview out of it without any context, knowledge, or history. Like the tweet says, “Getting a lot of ‘Boss Baby’ vibes from this...” or this joke format’s logical conclusion, “getting a lot of shadows on the cave wall vibes from this”.

A reversion to absurdity in lyrics (as opposed to lyrics that are meant to be understood by as many people with as little friction as possible) makes music mean more to me personally. Every time I played Dry Cleaning it was like doing Duolingo with a dead language, my language. This was a common strain of lyricism in ’90s indie rock (probably why Dry Cleaning lights up the same part of my brain that the Pixies do) and a very uncommon theme in indie rock today (outside of Black Midi and a few other logorrheic post-punk bands). It’s exclusionary, and some may see it as emotionally distant or hollow, but my largest emotional response to music this year came from not from hearing emotion rendered into song, but mostly out of jolted by a phrase, a sound, a style I haven’t heard before.

I’m wasn’t immune to bald emotionality. I wrote about the story I think Adam Granduciel is trying to tell with the War on Drugs, which is very simple and familiar. Both Adele and Jazmine Sullivan moved mountains with their voices alone. On the Armand Hammer album, Elucid spends a beautiful verse remembering a summer camp in the Catskills. Angel Olsen and Sharon Van Etten’s “Like I Used To” — probably my favorite song of the year — is all past, no future. I’m lured into the past so easily. It’s so great there. I love it! We should all go sometime.

“And somehow the music we all grew up listening to doesn’t relate to our adult reality and our new dreams.” I don’t think this is prescriptively true, but what I am trying to do is be on path of musical discovery that is increasingly less determined by what came before it. As I age, leave the city, separate from my past, settle into five years of an outstanding marriage, really get into cooking farrow, try to be a better more considerate person for my friends and family I am always asking myself this question: Does our identity determine what we like? Or does what we like determine our identity? It’s harder for me to hold onto an identity that I love, one that I think is interesting or valuable. But I think who I am is someone who is constantly searching for something to define himself by.

Which is good enough for now.

1. Dry Cleaning - New Long Leg

2. Turnstile - GLOW ON

3. Pharoah Sanders & Floating Points - Promises

4. Armand Hammer - Haram

5. Low - HEY WHAT

6. Jazmine Sullivan - Heaux Tales

7. Mach-Hommy - Pray For Haiti

8. Giant Claw - Mirror Guide

9. Yasmine Williams - Urban Driftwood

10. Chris Corsano & Bill Orcutt - Made Out of Sound

11. The Armed - ULTRAPOP

12. black midi - Cavalcade

13. Mdou Moctar - Afrique Victime

14. The War on Drugs - I Don’t Live Here Anymore

15. Nala Sinephro - Space 1.8

16. Skee Mask - Pool

17. Dean Blunt - BLACK METAL 2

18. dltzk - frailty

19. Faye Webster - I Know I’m Funny haha

20. The Weather Station - Ignorance

21. Iceage - Seek Shelter

22. Body Meπa - The Work Is Slow

23. Rosali - No Medium

24. PinkPanthress - to hell with it

25. Sam Gendel - Fresh Bread

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2020

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2019

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2018

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2017

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2016

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2015

Favorite Albums of 2020

When I met my new neighbor, Wayne, he told me he doesn’t wear sandals that were made in China because of the poison that seeps into your feet, presumably by osmosis. He and his wife (whose name I forget) have a lightbox of the Virgin Mary in their backyard that stays lit all night long. Our other neighbor, Shannon, is a wine mom, in that she is a mother who sells her own brand of wine out of her house. I get the feeling her husband (whose name I forget) doesn’t like me, but all the niceties and welcome-wagoning that we’d secretly wished to have had with our new neighbors were stymied by the pandemic, which—I’m sure—prevented them from inviting us over for a drink or bringing us some cookies when my wife and I moved into our first house in July, on the hottest day of 2020.

Both neighbors (whose names I remember) are old enough to have sired me, as is pretty much everyone who lives in Verplanck, New York, a small hamlet just south of Peekskill. Our town is so small we don’t have a mail truck, so every day I walk down to the post office to get my mail from the p.o. box, auspiciously numbered 808. To round out the hamlet: The post office shares a wall with a hair salon, there’s Angela’s Deli run by the namesake’s son Tony, a bodega (only up here you call it a “store”), a seemingly fine Italian restaurant, and a marina with more than a few Trump flags hanging off the masts. That’s about it. “This is our life now,” we often find ourselves saying to each other, always with varying degrees of bemusement, relief, and resignation.

The first five months of the pandemic, the final five months we spent in our apartment in Crown Heights, is a blur. There were a lot of lines and sirens and fireworks. We barely left our place at all. I don’t think I have anything novel or unique to say about that time yet, though I was lucky enough to have been a runner and used running as an emotional crutch. One day in late March, I ran a big loop around the city, 18 miles with a mask over my face, over empty bridges through a deserted Manhattan, and back again. The only other people out were skaters gliding roughshod over empty streets and a few other runners, all masked up. I made a bunch of running mixes during this time, and put “Kim & Jessie” by M83 on all of them. That’s the only song I remember really having an effect on me during our Brooklyn quarantine, I must have listened to it 30 times. I kept waiting for it to make me cry; it never did, but the thought of crying always occurred to me. That’s the best way I could describe quarantine.

My favorite album of the year is the Microphones’ The Microphones in 2020. It’s an album, but it’s also a song, and arguably a podcast. Phil Elverum, who performs under the name the Microphones and Mount Eerie, wrote this uninterrupted 45-minute piece of music that asks a lot of the questions I asked myself this year: Why do I do this? What is the meaning of this? A self-referential dialogue with oneself and the past to uncover some deeper truth to life: The Microphones in 2020 appeals to that weepy, beardy, Knausgaardian heart of mine. And now here I am futilely chasing after this album, fumbling to find the words and make something of my own in the dim of its enormous shadow.

I realize I have a lot bottled up in me from this year of inertia. I was unable to express myself quickly and with alacrity. I have perhaps even spent an entire year lying through my teeth. So forgive me, please, and indulge me, please, because it feels good to sit here and type without censorship or feeling the need to wrap things up with a button or joke, or to chat cautiously among co-workers so as not to unsettle or burden them. It feels good to dig under my skin and look around and apply pressure to every question I ignored this year. This indulgence has been afforded to me by Phil Elverum, who also gazed deep into his navel for the better part of an hour and returned with an album about the creative process, the vocation of music, self-mythology, spirituality, eternity, vulnerability, bottling some unnamed emotion and studying it intimately. He went back to the well and returned with some semblance of what his work meant and what his time on this earth has been about. (This kind of indulgence has also been afforded to me because is a personal blog.)

These big themes of art and music remain so interesting and so mysterious to me. Perhaps because they are some of the worst, most unadvisable themes to write about: Gather round let’s talk about what art means, why we’re here, what feeds great wellspring of creativity. Everything becomes wispy and cirrus, prone to sweeping generalities without much care for ideology and wit and pizazz. No, none of that, let’s just languish in some Proustian temporal mood evoked by, like, the cold rubber smell of a bike tire or a cloud obscuring the peak of a Pacific Northwest mountain. I still connect with the normal, tactile emotions in music: heartbreak, love, sex, death, identity, drugs, money, agency, anger, indiscretion, all those things that pop music and humans need to feel seen. Pop music exists to make people feel comfortable in their bodies. Someone put a melody to exactly what you are feeling, and, well, isn’t that pretty neat?

But I often find myself listening to new music and I think: Why are you making this? What are you doing here? What do you want? These are things I overlook because I’m afraid to be seen as someone who takes music too seriously. Most pop music is for children and most music is not that serious, yes, but if it’s not, then why have I dedicated this era of my life to it? To be dipped so fully into that question by Phil is such a generous gift during a year where I sat at length with my own thoughts, kneading my brain like so many balls of sourdough. Phil’s project helped me to refocus and recenter what I love about music, what I find so powerful about it: it is always something unspeakable and unknowable. It’s the search for the divine, a glimpse at something bigger, “the true state of all things” and it’s a journey I felt so compelled to go along with because it is the one thing I feel music can actually seek to answer. Moral instruction, political efficacy, self-pity, self-aggrandizement, self-discovery—ok, sure—but what about the stuff you can’t simply apply to this version yourself? What happens at the end? Someone put a melody to exactly what I was feeling.

This has become my predicament as a listener and music writer over a certain age: How do you be rigorously honest with the life you’ve accumulated while connecting with popular music that is being created now? In some sense, I wish I could do The Microphones in 2020 in reverse: instead of tracing a history that led me here, I’d just simply erase every memory, every song, every note I’ve ever heard and just begin again. Empty it all out to feel what a young person feels. No longer would I be on this path toward ambient jazz, psych-folk jam music, loop revival, prog-hardcore, 45-minute folk soliloquies about music itself—just let me be reborn into Jack Harlow, TikTok challenges, and shitty bedroom pop, into a world where there is no linear connection to the past just a rapid-fire, iterative present.

Konstantin Stanislavski, the great fin de siècle Russian theater man, coined the phrase The Magic If. The idea is that as an actor you have to approach your role with this underlying thought: What would I do if I were this character. That’s the mindset I have at work when listening to music. What would I think if this music was made for me? It’s a byproduct of my job and needing to have a handle on a wide array of genres, to have a baseline of empathy for its creators and listeners, and to be able to give feedback to writers as they move organically through their own discovery. It is the single best part about being a music editor: Learning how to listen to music through the lens of a younger writer. But for me personally, for my own path, it’s exhausting. (I feel guilty for thinking that.)

On election night, I couldn’t bear to watch live coverage of the returns, having defamiliarized myself with the toothless, improvisatory, “In conclusion, Libya is a land of contrasts” cadence of cable news. So I laid down on my bed, put on headphones, and listened to The Microphones in 2020. Twice. It was the most comforting thing I could think of doing, to just be swept away in this foggy story of how this music that means so much to me and so much to Phil came to be. I understood finally: the acoustic strumming panned in the left and right channels during the initial seven-minute invocation is an act of hypnosis. The syncopation mirrors this tumbling backward through time, bumping against dates, people, memories, feelings, until Phil begins the story.

The two moments that stand out to me are these: One, when Phil recalls a lyric from “Freezing Moon” by Mayhem: “the cemetery lights up again, eternity opens.” I’ve started keeping a list of lyrics that I enjoy every year, just scraps and bits that stuck with me. One constant that I cherish among all types of music being created now is the transparency by which artists share their influences. Music is, above all, about other music. (I always think it’s funny when someone describes a film as “a love letter to the movies” as if all movies aren’t a love letter to the movies, as if all art is not here to serve at the feet of the art that came before it.) But especially now, music is chiefly about other music: the mimesis of social media and the exponential sorting of song data and playlisting relies on its relation with other music. To this end, I’m always charmed when an artist just mentions how much they love another artist in a song, baldly, whether they were listening to a certain song on the radio, or sampling a lyric, or like Phil, saying he “saw Stereolab in Bellingham and they played one chord for 15 minutes. Something in me shifted. I brought back home belief I could create eternity.” It made me feel that in our ecosystem without live music is still this one great interconnected superorganism that speaks secretly to each other through the soil

The second moment that will stay with me always is at the conclusion, this line: “I hope the absurdity that permeates everything joyfully rushes out and floods the room like water from the ceiling, undermining all of our delicate stabilities, admitting that each moment is a new collapsing building. Nothing is true but this trembling, laughing in the wind.” No single moment of music gave me more comfort than this, this ridiculousness, this joy, this laughter at the world. My terrible habit of “gaming everything out”—until I reach the conclusion that the earth is irreparably damaged by capitalist industry and our democracy is incapable of mitigating the destruction and every human is now born into loss, steeped irrevocably in the sins of their fathers, sent into a life angled at a precipitous decline that may be tipped up a pathetic few degrees by various legislative measures but always will be slanted toward total global destabilization—is “not very healthy,” many would say. But I look at this line and I smile. It reminds me of another song: If that’s all there is, my friends, then let’s keep dancing. This line, this album, it really meant something to me this year. I hope you found something similar during this fucken year. And I really hope I learn the names of my neighbors, somehow. Dicey at this point.

The Microphones - The Microphones in 2020

Fiona Apple - Fetch the Bolt Cutters

Waxahatchee - St. Cloud

Nubya Garcia - Source

H.C. McEntire - Eno Axis

Dogleg - Melee

Destroyer - Have We Met

Moses Sumney - grae

Special Interest - The Passion Of

KMRU - Peel

Beatrice Dillon - Workaround

Alabaster DePlume - To Cy & Lee - Instrumentals, Vol. 1

Rio Da Yung OG - City On My Back

Bartees Strange - Live Forever

Kate NV - Room for the Moon

Jeff Parker - Suite for Max Brown

The Soft Pink Truth - Shall We Go On Sinning So That Grace May Increase?

Soul Glo - Songs To Yeet At The Sun

Angel Bat Dawid & Tha Brotherhood - LIVE

Roc Marciano - Mt. Marci

Lomelda - Hannah

The Killers - Imploding the Mirage

Chris Forsyth / Dave Harrington / Ryan Jewell / Spencer Zahn - First Flight

Phoebe Bridgers - Punisher

Oneohtrix Point Never - Magic Oneohtrix Point Never

Country Westerns - Country Westerns

Favorite Albums of 2019

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2018

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2017

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2016

FAVORITE ALBUMS OF 2015

Favorite Albums of 2019

In June, I took a backpack, some supplies, and camped under a grove of hemlock trees. Find a hemlock grove and you will have great comfort through the night: Their fallen needles decompose and acidify the soil so that the ground is soft and free of understory, their twigs are coated with a wax that acts as a natural lighter fluid for starting a campfire, the dense composition of the branches and needles in their canopy creates a natural umbrella from the rain. After a few-hours hike into the southwest corner of the Catskill Forest, having bushwhacked a mile off a hunting trail near the bend of a river, where tiny wild strawberries bloomed in sunlit patches, I slept under a tarpaulin suspended between two trees and staked into the pillowy forest floor.

The owls had stopped hooting and it was still dark when I woke to the pouring rain breaking through the evergreens’ shelter and pelting my own. A stream of runoff from the tarp had begun to soak my feet in the sleeping bag. When I moved away from the puddle and readjusted my position under the shelter, I laid back on my sweatshirt-pillow and listened to the click-clack of rain for a while. A smile grew on my face like a time-lapse shot from a nature documentary. I felt apart, miles away, yet so full and surrounded, running on the richest calm that sent joy through down my legs and through my fingers. I chased the feeling all year.

It was a struggle, though, knowing that if I always indulged in this nature escape, I would be abdicating some kind of civic responsibility and exercising some immense privilege. There was that New York Times article about Erik Hagerman who, after the 2016 election, decided to ignore the news, extricate himself from society, and be really obnoxious about it. While everyone was channeling their rage and newly sprung activism into yelling at him for his extreme opt-out, I felt this shameful knot in my gut. What’s so wrong with leaving? I would do that. I would absolutely do that. The data, the chatter, the static, the invective, the unreality of a day spent on the internet, it all just churns beneath my work life like a white noise machine that, instead of helping you sleep, keeps you awake.

While my relationship to music is stronger than ever, my relationship to media has become…bad. This recursion, the memification of all input, the rote familiarity, the “psychological lubricant” that just glides everything into its place has made me want to occupy my free time with something more natural. It’s no wonder I spent more time running than writing the year. I can’t write my way out this stultifying time in my life, so instead, I run. Or I dream of becoming cliché just to be apart of something else: moving to the forest to hear nothing but the wind through the pines the rain on the window and my records every day.

The music that meant the most to me in 2019 was defined by the call to leave, the pull to stay, and the risk of changing. Big Thief’s first album of the year, U.F.O.F., was the idyll, the grassy space where any thought can live or die without worry. It was the dream of leaving the pavement for the farm or whatever, something like that night out in the wilderness under the tarp. Real magic glows in the margins of U.F.O.F. with its little production flourishes, a runic musical language from a forgotten age whispered behind every song. Before I published my review, I asked Big Thief’s publicist if they’d tell me what sound that was, exactly, that opens “From.” It was mesmerizing to me, it sounded like a marble stuck in a broken Rube Goldberg machine. The band declined to tell me what it is, and I’m all the happier for not knowing.

What pulled me back to the city was David Berman. His first and final album as Purple Mountains, released just before he killed himself earlier this year, is all about writing through it. To not run away, but to sit a little while within it and make something out of the fire that surrounds you. Sink into the flame. Let it swallow you. Become it. This album is so inspiring to me as a writer, listener, critic, and as a person who struggles with expressing the low dysthymia that lives in me at all times but goes unsaid because I do not want to seem like I am not grateful for the life I live and would rather perform the more valuable, fun, joke idea of myself. The warm turn at the end of “Snow Is Falling In Manhattan” makes me dizzy and teary every time I hear it. The detail, the humor, the hatred, the love; under God there is no greater knowledge of one’s life than Berman.

His songs sometimes look like a rough draft: A thought, then a clarification, then a conclusion. But they are carefully arranged, every word painted into the frame with generational patience. His command of meter and language is so vast and exceptional that he oscillates from the assonant and lyrical “icy bike chain rain” and “salts the stoop and scoops the cat in” to these Strindberg-meets-Wilde limericks like “how we stand the standard distance distant strangers stand apart” and “if no one’s fond of fucking me maybe no one’s fucking fond of me.”

I found myself walking around in both these albums even when I wasn’t listening to them. One a dream of who I could be, one a reminder to be myself right now, no matter how much I may not like it. In Quinn Moreland’s terrific review of the new Beat Happening box set, she opens with a quote from Calvin Johnson that has stuck in my craw since I read it: “I know the secret: rock‘n’roll is a teenage sport, meant to be played by teenagers of all ages—they could be 15, 25, or 35.” Since I was young, it was instilled in me that I was to be an adult. Being a teenager is something you will soon grow out of, and then you will finally become something true and worthwhile. Would enlightenment arrive, finally, if I simply sat in a Barcalounger astride a book of crosswords and a John Irving hardcover while listening to The Diane Rehm Show?

This is obviously absurd, but it is coded into my brain. I have a difficult time being young and giving credence to the feelings of youth. Not out of jealousy or fear—honestly!—but out of a hierarchical, chronological notion that you grow up and outward. Time makes you a pioneer. You take risks, fail, become someone greater and more complex the more you gather and shed the simplicity of youth, the oxygen of the best rock’n’roll, like Beat Happening. I fell newly in love with Beat Happening this year after years of dogging them for “not having a drum set” or something unfounded. I’m lucky to be surrounded by Calvin Johnsons in music writing, forever-youngs playing the sport of teenager while I try to be a good coach.

This is probably why it took me so long to come around to Vampire Weekend’s Father of the Bride, breaking wild new ground for a band I have loved my whole life. I foolishly, fearfully was lukewarm about the record when it came out. I thought it lost some of the elegance, whimsy, and transportive specificity of MVotC, but I kept being drawn back to it because I trust Ezra Koenig as a songwriter. I am wise enough to know now that sometimes it’s not the band’s fault, it’s my own fault as a critic. Over the year, I came to know the language of the album more, the backmasked drums, the twang, the whole mood as if Prada made a rope sandal, the tactile songs about old power and new love, studying the uncool sectors of jam bands and classic rock to move forward, to age gracefully and stay young at the same time. Vampire Weekend, four albums, in stores now.

The idea of getting out of patterns, willfully changing behavior to claim some new ground has overtaken my mind. The other records that really meant something to me were more “out” than years past: black midi’s teenage inhibition, Aldous Harding’s wild pen, Tyshawn Sorey & Marilyn Crispell’s hypnotic game for drums and piano. For anything that did not rattle my soul or float into my post-punk wheelhouse or sound as expensively ornate as Ariana Grande or Lana Del Rey, I was moved by music that fought, really fought against patterns. I was drawn to records that bucked an increasingly programmatic world, something that had the touch of chaotic human thought or, in a horseshoe-theory way, by A.I., as in Holly Herndon’s case.

Maybe I am making my fourth album, trying not to rest on the laurels of past success while still trying to be truthful to who I am at 34, even if it doesn’t “play well” to an audience. Here I am, in the abyss of my own critically maligned mid-career, anchored by age, too focused on my side-projects (running marathons, fucking around on twitter) but willing to untie old knots to become someone new. I might move to the country or stay in the city. I might get older or try to get younger. The ceiling is unlimited and it’s paralyzing but here I am, frozen, writing through it, thawing, little bit little.

Big Thief - U.F.O.F.

Purple Mountains - Purple Mountains

Vampire Weekend - Father of the Bride

FKA twigs - MAGDALENE

Aldous Harding - Designer

Mannequin Pussy - Patience

Bon Iver - i,i

Kim Gordon - No Home Record

Lana Del Rey - Norman Fucking Rockwell

The Comet is Coming - Trust in the Lifeforce of the Deep Mystery

Brittany Howard - Jaime

Holly Herndon - PROTO

Billy Woods - Hiding Places

Fontaines D.C. - Dogrel

black midi - Schlagenheim

Inter Arma - Sulphur English

Polo G - Die A Legend

Fennesz - Agora

Ariana Grande - thank u, next

Junius Paul - Ism

Thom Yorke - ANIMA

Richard Dawson - 2020

75 Dollar Bill - 75 Dollar Bill

Squid - Town Centre EP

Tyshawn Sorey & Marilyn Crispell - The Adornment of Time

Favorite Albums of 2018

Favorite Albums of 2017

Favorite Albums of 2016

Favorite Albums of 2015

Marathon

For seven months I haven’t met a day without soreness or left it without exhaustion. Whether nursing an inflamed achilles tendon or dealing with a pre-arthritic runner’s knee or just a general ache from a speed, distance, or strength workout, my body, at 34, has become the site of a shady remodeling project, a real gut job like someone’s trying to flip me for cash. I ran my first marathon in the spring, came in under four hours, and tomorrow I begin training for my second marathon. The idea of running two marathons in a year would have seemed preposterous were it to cross my mind at any point during my life, and here I am, 456 earned miles under my feet since January, hoping to have a good day at the New York Marathon in November.

Becoming an athlete—a class of people I consider myself a part of because of both the constant soreness/exhaustion as well as occasionally not drinking because of a planned workout—has been an all-time great decision, right up there with marriage and seeing OutKast on the Stankonia tour. Unlike becoming a creative—a class of people I consider myself a part of because I occasionally smoke weed and have an astonishing ego—the athlete actually sees measurable progress. Put in work and see results in the body. For instance, mine has gone from writerly schlub to that post-schlub road-biker look with a baby-fat gut and weirdly jacked thighs; guy who walks into the corner store dripping sweat and tries to buy a huge thing of coconut water and an RxBar with Apple Pay but can’t get the thing to show up on the phone and his holding up the whole line.

But also: Put in work and see numbers. Real numbers, times on a stop watch, data logged, arrayed, and analyzed. I have a record of the same workout I’ve done for the past year and to see my pace quicken, to see my heart rate decrease as I shorten those times little by little has been the most rewarding thing. They say that you need a hobby if you are going to be a creative type, something where you can be objectively successful instead of subjectively and hopelessly typing words trying to convey meaning and style. Cooking, gardening, woodcraft, Starcraft, whatever. Long-distance running has become my hobby, the tangible and tactile activity that exists alongside this indestructible and altogether unhealthy desire to be regarded as a writer and editor of note.

I wasn’t necessarily an athlete growing up: I played sports because that was the main after-school activity you could really do in my town other than Cub Scouts (too churchy) or 4-H (too muddy and too churchy). So I sportsed, but by the time the youth rec league transitioned from charmingly participatory to actually competitive, I was slotted into the also-ran positions in each one: soccer (full back) track (3000m race) and basketball (guy who’s encouraged to pass it). I was the utility player who clearly didn’t have one of two things that allows young people to excel at sports: the drive to practice or the innate coordination to not have to practice. When I told my dad I wanted to quit baseball, it led to one of the biggest drag-out family fights in our history, the kind everyone looks back on with eyes down and utter shame.

So I grew into an oblong creative-type. Soccer practice turned into play rehearsal, baseball turned to transcribing Stan Getz solos, getting exercise was replaced by a life of the mind which included a lay interest in fiction while getting high and ordering two double cheese burgers at McDonalds on the way back from band practice. It all flowed easy, there was no one disappointed in my skill level, no teammate disappointed in my fear of the ball, no pithy orange slices to factor into the process.

Until this year, I didn’t really know what it took to be an athlete. I had worked out, yes, I had even gone to the gym for a couple years, but that was more out of vanity than any kind of goal (the goal was to look attractive enough to be able to play a convincing Romeo, a contrapuntal action to distract from the fact that this Romeo was going bald). Insanity is doing the same thing and expecting different results. Athleticism is, in my understanding of it, doing the same thing and expecting different results—and actually getting them. The first day running on the road is misery. You are moving as if a bungee chord is attached to your back. But each day the bungee loosens until it’s gone, as long as you keep doing the same thing, keep setting the alarm, keep committing to honing the rhythm of the day when you are getting up to run and refining the posture and movement of the legs and body. 800-meter repeats, 6 times up the hill, 4-mile loop at pace. Running is an exercise of repetition and trust that if you continue to do the workout, it will get better and better. Fall into the pattern like a trance, add a couple speed workouts, and suddenly my 34-year-old body is using oxygen like a goddamn 20-year-old.

This, I think, has given me perspective on the struggles of media and music. (Should also add this is why writers are encouraged to do a real hobby or thing, to find new perspective through the eyes of a subculture and use it to add dimension to blogs and essays.) In the worst of days online, it can feel like we are trapped in a repetitive, recursive nightmare. We struggle with how to process the same information—delivered in the same kind of way—over and over because nothing seems to be changing. Another day, another spate of horrifying or banal stories and emails delivered with roughly the same tone and commented on wryly or cynically by the same people. At worst, the information becomes toxic and elicits an unwarranted negative response to the sender; at best, we tie our brains into some mariner’s knot to try and have a genuine response to the information. We employ cynicism, nihilism, irony, anger, and contrarianism to try to respond to this sameness. We elide normal response in favor or something so layered and inscrutable as to be entirely without actual meaning. But do we grow? Do we get faster? Do the numbers really go up?

In music, repetition evokes hypnosis and familiarity—the warmth of a house beat, the comfort of a vi, IV, I chord pattern. In writing, repetition evokes a motif, a signal to pay attention this this, or a crutch a writer relies on. In nature, repetition forms in snowflakes and snail shells, a result of mathematics and natural selection. The phenomena of repetition and recursion are so often signifiers of meaning and beauty, except when it comes to how we consume media. Because of the pace of digital media and publishing, information has to constantly be packaged in different ways else we over-familiarize ourselves with it and the package begins to curdle. Every day we are recalibrating ourselves to the speed with which we need to absorb and familiarize ourself with new news, new emails, new music, books, movies because there is no governor on the amount of information we can have. When I’m feeling a pain in my ankle on a run, my body brain and body is telling me to stop. When I’m blithely checking Twitter before bed, I don’t have any reaction that tells me I have already had too much information for the day.

The term “brain worms” is employed as a kind of in-joke when someone on Twitter leaps to what seems like the most absurd, layered, reactionary, referential response to a piece of information. Mostly “brain worms” is just what happens when you think the online world is exercise, when you believe you are accruing something or making the numbers go up, when in reality you just loading an overworked, injured brain and nothing is changing. Everything feels recursive because you cannot process new information.

Running has made me more sympathetic to an honest response, to patience, to the idea of approaching the same thing with new eyes. At the end of a long 14 mile training run, knowing that it is a distance greater than a half-marathon, that I am just out here doing the work, running a loop, slowly strengthening and building to do better the next time, I feel better than any one moment in life outside of getting some writing done.

Afterword: Draper Lulusdottir

On a scrap of paper stuck to the side of our fridge reads the contact information of a cat psychic who first informed us that our cat, Draper Lulusdottir, might be haunted by spirits from another realm. Draper was the only tuxedo cat of her three siblings, all of whom were snow-white just like her mother, Lulu. Lulu gave birth to Draper inside a haunted museum in Fairfield, Tx., one possible location for a television show about archeologists that my wife Marion was pre-producing at the time. Draper was adopted by Marion on the spot and ferried back to Brooklyn where they lived and would later welcome me into their family.

Draper died in the veterinary hospital last Thursday after a lifelong battle with an undiagnosed neurodegenerative disease. She was 8 years old.

The time she spent in this realm with me and Marion can be sorted into three eras. There was first the comfort era, beginning when Marion adopted this six-week-old kitten shortly after Marion’s father died. To her, Draper was a bridge to adulthood and autonomy, a shock of black and white fuzz that would be her charm and her charge. Here was this pouty-faced, sad-eyed kitty of the South that brought so much joy into Marion’s life. Draper dampened the grief with affection and love. She was a playful and rambunctious, a boilerplate lovable young cat.

Then Draper became a teen and stayed a teen for the remainder of her life. She lived in this sulky, passionate, sometimes aggressive state that was, above all, very funny. In the past few days, Marion and I have talked about just how funny she was. Not like prat-fall funny (though she would treat us to those) but kind of like a ‘90s Janeane Garofalo funny. She was so humorless as to be hilarious. Draper—just a cat, helpless and pure—put up this totally unfounded angsty front like she drew all her power from wearing platform boots and a ball-chain necklace. Draper became goth. She was never sly or clever or feline. Her fluffy tail never swished in the air as she wove in between your legs. Instead, she trundled around in slow, straight lines, prone to long periods of sitting and staring into the middle distance. She was awkward and earnest and, in private, an unbearably loving creature.

What started to happen to her as she turned 4 or 5 was something that to this day is inexplicable. The haunted era. She would still run, play, even purr on occasion. Though every time she heard a sound coming from someone’s cell phone, or a thin signal of noise coming from computer speakers, or even just a character talking on the phone on television, she would come racing in from wherever she was and try to attack whoever was in the room. We didn't know why this started happening, but we figured it had something to do with how her brain registered that particular noise. Maybe it was that specific frequency she just absolutely hated, nails on her chalkboard. So there we sat, our thumbs resting nervously on the “mute” button while watching television, thankful for any period movie that existed before the use of telephones. The “Don’t play YouTubes on your phone” rule was quickly told to guests, to be disobeyed at their own peril.

Around this time, Marion and her vet (and a crack squad of professional psychics and cat behaviorists) were working so hard at trying to diagnose what exactly was causing this. Was it a late-onset attitude problem? Was she aurally hypersensitive? Was it the ghosts of the museum? Marion was an early benefactor of an album of music “scientifically” meant to soothe cats with anxiety. We played the album for her, which sounded a bit like average new age music with purring added in. Around the house were several aromatherapy diffusers that were meant to be holistic solutions. We tried Prozac for a while, both hidden in her wet food and syringed into her mouth. We talked calmly to her (she was such a talkative cat, so vocally expressive). No two words came out of our mouths more than: “It’s ok, it’s ok, it’s ok.”

We told people she was haunted because that seemed an easy shorthand for something so mysterious, the way the Vikings thought a solar eclipse was a giant sky wolf trying to devour the sun. Part of us knew this myth wasn’t true as she began to lose feeling in her front legs. Soon she couldn’t make it up onto the bed, or the couch, or into the litter box. She was floor-ridden, shooting ice from her eyes up at the pigeons perched on the roof of our building. Her gait became halting and iambic. Her vet found nothing physically wrong with her so we took her to a neurologist who still couldn’t pinpoint a problem, but told us it was something in her brain or spine. She assured us Draper was happy and painless, until her final days when she lost mobility in her back legs and could no longer move.

We told ourselves Draper was haunted because it was easier than a fatal unnamed neurodegenerative disease that made her lose control of her legs. It sounded better on paper. It sounded better in anecdotes. It sounded better in the logline about our cat Draper. It sounded better than “Kitty M.S.” I believed it because she was truly a magical cat. When Marion and I would visit other cats who were normal, aloof, and spry, bounding from floor to kitchen counter to top of fridge, we’d laugh and say to each other, “Remember what almost every other cat is like?” We’d come home to our little lump of laundry plopped on the floor, our chunk, our queen, our babe, and know that she was the best thing that could ever happen to our family. She supported us. We would fall down without her.

What made me believe, in the end, that she wasn’t haunted was in the final years of her life, her aggression abated. The loving era. She grew more docile and affectionate to not only us but our friends who came by. She knew that she relied on us as caretakers and knew that we needed her as the constant of our family, the third leg that allowed our house to thrive. Inside Draper’s brain was something pulling her body away from her control, but she never stopped looking at us with eyes so full of love and need. In her final months, she was overflowing with love. It was serene to see this creature be such a pure medium to a place from which love comes unadorned with qualifiers or conjunctions. It was love, period, something we were blessed to have witnessed. By the end, she didn’t attack when she heard a speakerphone. It was like the affliction had left her, that she had exorcized it herself so that she could give us everything she had in this world she so briefly found herself in.

After-afterword: A perfect day in Draper Lulusdottir’s life

Wake up nestled in the crook of our legs, ensuring that she was well-rested and that we had a fitful night of sleep, fighting for space with her on the bed. A tray of salmon for breakfast. Time alone with her stuffed Bear so she can howl with him locked in her jaws in a song of violence and ecstasy. An uninterrupted nap in on a soft device that slowly follows the ray of sunlight coming through the window across the room. A tray of shredded chicken for lunch. A pigeon, a squirrel, and a silverfish each letting her think she is better than them. Listening to that special purr-age music for cats, sure, why not. An infinite series of connecting rooms, each with one door she can gently paw open. A fresh load of wet laundry draped over a drying rack so as to make a cave of smells for her to enter and explore. A plate of melted ice cream for dinner.

Favorite Albums of 2018

I think Low stood unflinchingly in the wake of the year. Braced against a torrent of insanity and instability, Double Negative inhaled from a toxic bong this warm Trumpian exhaust and sounded exactly like 2018 felt: corrosive, febrile, weightless, unclear, a mix of signal and noise. Its production is the very sidechaining of modern life—a succession of deep thuds that briefly suck the air out of everything around it, one push alert at a time, doomed to repeat until finally, blessedly, sadly, it ends.

What a marvel that for a band’s 12th album—an album far beyond any narrative or career arc—they come alive by frying their sound until signal and noise are almost inseparable. It is music for a world abrading into fragments of hope and fear made from three Midwesterners who’ve been doing the indie rock thing for over two decades. It was Low. (Low. Low! Fucking sleepy snowy slowcore Duluth, Minnesota's own Low. Who covered this bet?) It was Low who led us to the heart of the year, covered in foamy alkali so that it didn’t beat so much as it tolled and tolled and tolled.

Here’s a theory: We are increasingly compelled to create using the purest signal possible so as to be heard among the noise. We want to express ourselves with fidelity and clarity as a means of self-preservation, aggrandizement, validation, and empathy. The purer the signal, the more listeners we get, the greater our reach. This is pop music. This is safe writing. This is treacly network dramas. This is what is popular and known. This is what most of the country receives, a yawning signal of understanding uncorrupted by the noise of life behind it. The further we are pulled toward the loud, hyperbolic poles of thought and feeling as signal, the more this purity becomes synthetic, like a sine wave, all of popular culture vibrating at the same familiar tone of 440 hz, the tone we tune our entire lives to.

What is so often left omitted is the noise we live in every day, a prismatic world of middles, in-betweens, and incompletes. Stops and starts, accidents, the smudge of a wasted day, a daydream interrupted on the subway by a stoned guy dropping bag after empty bag of Gushers at your feet. The emotional states we enter and leave throughout our day are so layered that to leave behind the noise of those transitions—so strange and unfixed to any one ideology or politics—would be to miss out on a catalog of feelings, a year defined by a thick ledger of fleeting moments.

Think of our emotional states like the signal to noise ratio, opposing outputs bound together in portions that change daily depending on the news, who died, what you accomplished at work. Joy tempered by misery, hope obscured by fear, action muted by apathy, truth drowned out by lies. DJ Koze is a master at these middle moments, archly funny and goofy, squeezing every drop of life out of antiques and thrift store finds, spun into a psychedelic groove. I would have loved for the brilliant Knock Knock to have been the emblem of this year. But no album reflected these middle feelings for me this year as dutifully and honestly as Double Negative.

It is not a particularly fun listen to go through this gelid, tannic album that pulses toward nowhere in particular. But following this record—its words of blood and ash, its production from the great BJ Burton who also designed the bulk of Bon Iver’s 22 A Million, its magnificently understated songwriting underneath it all—leads you to the deepest most barren acre in the frozen tundra of music. It’s beautiful and dreadful, the last branch on the family tree of rock, covered in hoarfrost. Alan Sparhawk often sings the word “always” as if he’s reckoning with all of history. Someone drowns at the bottom of a lake, and things fall into total disarray. It is a signal drowned by noise, the full comprehensive picture of an incomprehensible year.

I’m fascinated by this grey middle in a year where it felt as if the mantle was left untaken. It felt like a year of instability, cracks in the infrastructure, and a choking fog that signifies we are near the end of...something. What that something is no one can really seem to say: climate, jobs, democracy, online publishing, the word “chief.” An ugly gravity pulls us toward a corner around which something horrifying waits—the diner scene in Mulholland Dr. but stretched out for a year, inching toward an unspeakable monster, real or imagined. From this collective feeling, Low made truly new music and it was extraordinary.

Low: Double Negative

DJ Koze: Knock Knock

Beach House: 7

Arctic Monkeys: Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino

Kamasi Washington: Heaven and Earth

Iceage: Beyondless

Snail Mail: Lush

Noname: Room 25

The Armed: Only Love

Pusha-T: Daytona

Let’s Eat Grandma: I’m All Ears

Flasher: Constant Image

boygenius: boygenius

JPEGMAFIA: Veteran

Robyn: Honey

Kacey Musgraves: Golden Hour

Earl Sweatshirt: Some Rap Songs

Drakeo the Ruler: Cold Devil

Mitski: Be The Cowboy

The 1975: A Brief Inquiry into Online Relationships

Makaya McCraven: Universal Beings

Father John Misty: God’s Favorite Customer

Stephen Malkmus and the Jicks: Sparkle Hard

Sons of Kemet: Your Queen Is A Reptile

U.S. Girls: In a Poem Unlimited

Sidney Gish: No Dogs Allowed

Bad First Drafts

Originally I thought it would be funny to write a review of the Greta Van Fleet album in this overeducated, bloviating, Richard Meltzer ’60s male critic type voice, only he thought Woodstock 99 was the one defining moment of rock music. The joke kind of fizzled out and ultimately didn’t make any sense and I couldn’t really tune it how I wanted to. Anyway, bad first drafts usually are destroyed but I’m bringing blogging back so here’s this:

Rumsfeld Dreams & Greta Van Fleet

Let me talk at you about this dream. Haven’t had one like this since Donald Rumsfeld rat fucked us in Iraq, a purebred, seminal dream. Oh-h-h I used to dream about it: Rock, that is. Rock and, as they say, its concomitant roll. Many dreams. Lots. SEVERAL. Three, four a night if the drugs were right. Unsafe post-moral, post-structural, post-everything dreams, NSF the kiddies. This one, this new dream was a craven vision, legs and hair and guitar and c. that had me twirling all the way back to the dawn of rock.

The dawn: Woodstock 99, the first particle of rock, the font of primal unity, you know, the real thing. A rare weekend rich w. oxygen before Bush II (but after Sixteen Stone), when there was finally some hot spit on the ball again: Lit, Godsmack, Creed playing w. the Doors’ one and only Robby Kreiger, and the rock-and-ok-some-funk-too Chili Peppers’ climactic conflagration, a raw display of eschatological viscera.

You won’t find this in your shabby history book, but the toast of Woodstock was king skeezix himself, Josh Davis, he of Buckcherry, he of the aforementioned dream. Take Iggy Pop and pour uncut U.A.E. diesel down his throat and that’s J. Davis, the once and future savior of rock&roll (give it time). Most bands was red sometimes yellow. Buckcherry was Roy G. Biv every song. They contained It, possessed It, became It—rock, that is.

To the dream. We are sitting, ass on cushion feet on pilly carpet, at a Famous Dave’s BBQ somewhere in the middle of farm fuck nowhere and it’s Josh and me and Justin Hawkins (he of the Darkness). On the table: drinks, appetizers, a rack of ribs, you know, lunch.

Picture this trio: dressed tip to toe in leather and rings and shimmering aquamarine jewelry and J. Hawkings, J. Davis, and me J. Larson are picking at the pork when Davis, shirtless (natch) leaps right up on the table and holds aloft a bona fide compact disc, a relic, a wonder, a rarity. “Davis get down from there what are you doing man” Hawkings says, seraphic, salacious.

“Attention all you shit weasels I hold in my hand a CD full of sound and fury...”

Ah, enough w. this shillyshally, I don’t need to tell you what he’s holding aloft above the sweet teas and smoked comestibles: the new Greta Van Fleet album, Anthem of a Peaceful Army, you keen-eyed reader full of so much sparkle and pop. This is the THING. Not since Buckcherry did a band blow out all my lights. All of them. Every one. At the same time. These four nu-saviors from Michigan (home of the Rock whose name is Kid) well they’re not just Buckcherry or Wolfmother even JET hack-o-lites, they’re on level 99—far out, intergalactic, cosmic, you know, out there.

Woke up from the dream and I swear to you kid the disc was lying next to my pillow like I was supposed to make it eggs. Shit, had I known what it was gonna do to me I woulda went out and bought a ring that morning. Anthem took me away to the fecund fields of peace and love, ice and snow, the past and the future, time bending around every guitar solo this kid tries to seduce me with. GVF was everywhere in the dream and out of it. Rumsfeld can rot and so can dreams now that we have a new Anthem.

NB: I read an article about Greta Van Fleet comparing them to Led Zeppelin but I don’t hear it. What I hear are millions of streams on Spotify, an army coming back from the dead. I hear rock finally tolling the grave bells from underground, a genuine dead ringer.

The Cars - “Drive”

It took five albums for the Cars to write a song about a car. I’m in awe that Ric Ocasek dodged writing about cars for that long. Six years. Was it on purpose, was it conscious? “Drive” calls all this into question. You assume, well yeah, that’d be a bit spot-on if the Cars wrote about a car; Robert Smith never wrote about a cure and Morrissey never wrote about smelting. But cars, what a valuable songwriting card to give up.

Since the ‘50s probably, the car radio was—I’m assuming—the one portable escape kids had for their music unless they, you know, snuck into the soda shoppe at night and had a swingin’ jukebox hop. More versatile than the bedroom, the car became a sanctuary of pop songwriting, the location of kisses, death, heartbreak and long, lousy metaphors about sex. It was solitude, privacy, a way home, the way out, from “Dead Man’s Curve” to “Detroit Rock City” to “Little Red Corvette.”

I wouldn’t be surprised if the Ocasek just put the name of his band out of his head while he wrote this simple, exquisite song about the finality of driving someone home. It's an ending endowed with such a specific melancholy—two people destined to be together until, finally, they are not. It's almost like a stock character in a melodrama or an ancient Greek poem: that feeling. Ocasek loads up that feeling and places each question inside the car, stacking them one atop the other. Maybe driving someone home is the first step or the last step, but it’s the one tangible action that is requested, every other question hinges upon the chorus