Before I get into this, I want to reset the table, align the flatware, and make clear why I’m writing a long essay. I want to give you a better reason to read this. For seven years, I’ve been doing these year-end prologues to accompany my list of favorite albums. (You can find them at the bottom of this page.) Originally I was just writing little blurbs for each one, but that slowly expanded into protracted personal essays and grand unified theories of how the exact events of the calendar year led me almost scientifically to arrive at my favorite two dozen or so albums. These essays have helped me give shape to something that is increasingly difficult to measure: my taste in music.

My job demands I think about taste constantly, and squaring my taste with that of my colleagues and our readers is—as I see it in my head—an extraordinarily tense ballet. Taste is about many things, though it is arguably about everything: status, social capital, identity, class, income, environment, family, education, desire, fear. The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s rigorous but increasingly dated book Distinction is probably the leading, 613-page definition of “taste.” Bourdieu spends a lot of time theorizing about how class plays an important part in developing taste, that—among mid-century Parisians at least—there’s a pervasive working-class aversion to, say, avant-garde theatre or non-figurative painting because it’s unclear what these artworks are supposed to signify. Kitsch and pop art feel good immediately, whereas experimental art breaks down the conventions of what makes things enjoyable. If you don’t have a working definition of what makes pop and kitsch enjoyable, Bourdieu posits, it’s near impossible to understand a dissonant, arhythmic, asocial work that subverts it.

I’m not a sociologist, but I do play one in real life. And so I believe—said with a swirling of my hand and a gentle pull from a vape pen—that most negative responses to art are rooted in fear. Fear of social acceptance, fear of misunderstanding, fear of ridicule, fear of identity betrayal, fear of identity loyalty, fear of self, fear of youth, fear of death. Among the many pull quotes in Bourdieu’s book is this bit about dichotomies, about how taste is “first and foremost [about] distastes, disgust provoked by horror or visceral intolerance of the tastes of others.” This feels holistically connected to Hua Hsu’s riveting 2022 memoir Stay True, which acts as a personal case study in taste and friendship, Derridean différance and covalent bonds, Fugazi and Pearl Jam. As Hua recalls his turn-of-the-century friendship with a college friend named Ken, he feels at odds with this guy whose structureless, pop-kitsch consumerist taste in music and fashion doesn’t comport with his own rigid, leftist, anti-capitalist, “authentic” taste. Hua, the aesthete publisher of a zine, liked Pavement; Ken, a frat boy who wore his hat backward, liked Dave Matthews Band.

By the end of Stay True, you get the sense that instead of this being about how a collegiate odd couple came to understand each other by trading a burned CD of Under the Table and Dreaming for a cassette tape of Slanted and Enchanted, it’s that you perhaps already contain that which isn’t you. That when you love someone (a friend, a partner, a brother) with different taste, you realize, in the Derridean sense, that all that disgust and horror would not exist without its concomitant love and curiosity. It’s about the volatility of opposites, the ability to see yourself in someone else, subsuming them, becoming who they are. Near the end of the book, when Hua finds an auto-fictive movie script Ken had been working on, he sees a rendering of his persona through Ken’s eyes on the page. It’s the moment the molecules of two insoluble liquids go through some kind of alchemical reaction and become a distinct whole.

It’s in this vein that I believe true taste—at the most atomic level—is about friendship. Oh brother, how sentimental. How mawkish. How kitsch! Well, you see, over the past year, I’ve been keeping a playlist called COMMUNICATIVE IN 2022, where I compile a list of old songs that I have, in some way or another, found a new connection to. Some were added from spending time editing Sunday Reviews and reading about the writer’s relationship to it (Bonnie Raitt’s “Nick of Time”; Terry Callier’s “Golden Circle”). Some I found a new love for after hearing it used in a movie or TV sync (Joe McPhee’s song featured in the “defiant jazz” scene in Severance, for one).

But most of the playlist consists of recommendations from other people. Each song is a memory I recall vividly: Chatting on Slack with Sam about Karate and then later, Gary Stewart, or DMing with Schnipper about A.C. Marias, one of many bands I discovered on his indispensable Deep Voices playlist, or in a group chat with Mark about how much he thought Thomas Brinkmann’s “On Edge” reminded him of 100 Gecs’ “Doritos & Fritos,” or how someone at work made fun of me for never having heard Camp Lo “Luchini AKA This Is It” before our ’90s list, or Anna talking about how she really loved early Ezra Furman, or how Bill knows I like noodly stoner stuff on summer afternoons and sent over Jonathan Wilson’s “Desert Raven.”

Is this taste? This inscrutable playlist whose only throughline is a mysterious autobiographical appendix that I’m only cryptically sharing in an abridged form? It’s certainly more tangible to me than imaginary guesses at music that connotes some kind of social rank, or over-torqued posts or essays about music’s political efficacy, or wild swings at what, actually, the indie sleaze revival is subverting. It was easier two decades ago to say that you hated Dave Matthews Band because they stood for everything Pavement was against. It was easier for me in the retrograde, gender-conforming days in my rural high school to not like Britney Spears because she was commercial pop music for girls and instead spend my time listening to Dream Theater and Metallica, boy music with more notes. In the super-saturated, non-linear, algorithm-driven, personality-based music ecosystem that exists today, it’s increasingly difficult for me, in good faith, to like something because it is in opposition to something else. There are a handful of albums this year that still thrillingly kicked and thrashed from a defensive stance (Soul Glo, Special Interest), I still find myself in the thrall of nu-prog as a blunt tool against the tyranny of common time (Fievel is Glauque, Black Midi), and I will forever be in awe of the simple idea that a few people can sit one room and create, over the course of 60 minutes, music that serves a higher spiritual force (Jeff Parker’s Mondays at the Enfield Tennis Academy).

But in reality, because of social media and oversaturation, there is very little action or reaction in music. Billboard hits are either preordained by the money afforded to major label artists or bizarrely capricious. The latter songs bubble up from TikTok into an exponential viral snowball, fuelled by users making a safe bet by creating content using the most popular TikTok snippet there is, thereby having a greater chance people will view their own content. And on and on it goes. Songs are made popular by the individual desire to become popular.

Both of these modalities for chart success seem to exist in the vacuum of the individual song and the personality of the creator, not part of some broader musical era connected by a sound, theme, or trend. So what stands in opposition to this? Who will don the “I Hate Pink Floyd” shirt that sparks a movement that shifts the pendulum away from social-pop hits to give dimension to a scene whose admiration might connote good taste? I had hope for hyperpop, but that is quickly waning. I fear that the methods of Oneohtrix Point Never—my erstwhile sage of futuristic composition through recontextualizing the past—are now becoming a homogenized and common trope with other pop producers. I fear generative A.I. will probably take over large sectors of the music business. So what is this year’s “grand unified theory” of what music should be about going forward, something that can drive taste other than the friends we made along the way? I have one very small idea that I hope to expand into a larger thesis.

There’s a moment when Exuma’s 1970 song “Exuma, the Obeah Man” came on in the third act of Jordan Peele’s Nope. I started levitating. What is this, who is this, I am sure this is the greatest song I have ever heard. Exuma—I found out later—was a Bahamian-born singer who worked in New York and recorded a few records in the ’70s for a major label, when there was a small market for gravelly, leftfield psychedelic rock in the vein of Dr. John or Captain Beefheart. He never really took off in the mainstream, and while the artist born Tony Mackey kept writing and performing up until his death in 1997, his music remained mostly sought after by crate-diggers. The song Peele carefully selected for Nope is Exuma’s de facto anthem, an Afro-spiritual celebration full of stomps, clanks, whistles, and ribbits. It is a dark night on the beach, and there’s a fire blazing at its center.

I don’t even know if Exuma in Nope was my favorite movie-music moment of the year: It’s up there with the Clash’s dub version of “Armagideon Time” that appears (somewhat obviously in retrospect) in James Gray’s Armageddon Time or Lydia Tár and her wife dancing to Count Basie and talking about slowing the heart rate down and nitpicking the actual bpm of the song. But Nope is my No. 1 movie of the year, and my favorite of all of Peele’s movies thus far. It is not just for the needle drops (like when Kiki Palmer grabs a Congos record off the shelf) and the diabolically high concentration of band shirts (Earth, Wipers, Jesus Lizard, RATM) that are clearly playing to, well, geeks like me in the audience. But it is a movie full of big ideas that come from little unforgettable moments. A bloody shoe suspended in gravity suggests something OJ coins as a “bad miracle”; a Bahamian jockey in the first moving picture suggests a desire to give agency to lost figures in entertainment; a billowing, blood-sucking, polyester alien suggests the inability to capture a spectacle without it taking something from you in return.

Peele and critics refer to his movies as “social thrillers,” but Nope is also another type of genre, the latest in a long line of movies about making movies. People like me love these movies because, guess what, we love movies. From Singin’ in the Rain to 8 1/2 to Mulholland Drive to just about every Tarantino film, studios will seemingly greenlight any film loosely about the art, craft, or business of filmmaking. You like movies? Wait until you see a movie about ’em! Of course, what Peele has to say about movies and Hollywood’s history is far less rose-tinted and tinsel-strewn than his contemporaries. It’s a sharp stick in the camera’s eye.

It follows that I also love music about music. My favorite example is funk, whose songs are chiefly concerned about how good funk music sounds, the music you are presently listening to. In the ’70s and ’80s, rock bands built entire careers about how their rock songs rock, taking on a kind of self-appointed ombudsman role whose tautology was widely overlooked by their audience. Country songs remain very much about country songs, and are probably the most direct analog to movies about movies, given the propensity for both to be either nostalgically effective or charmingly clever. Rap is in constant conversation with itself, though rarely is this as openly acknowledged as it once was, partly because of the genre’s propensity to quickly evolve and eat the father, and partly because rap’s conversation with its past through samples has been diluted from an artform that built a new network of Black art to something far more Xeroxed and insignificant in recent years.

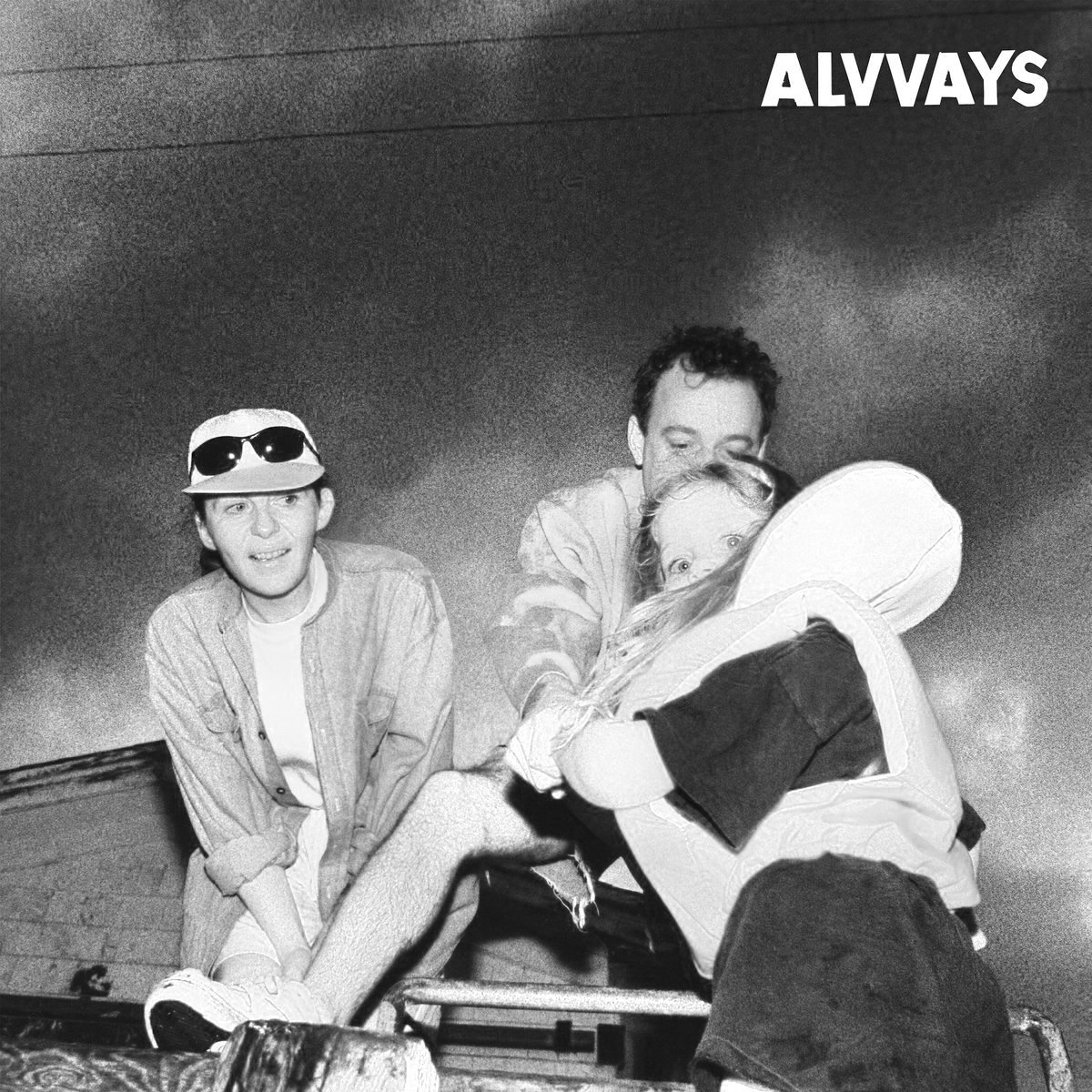

This was the year that I was drawn to music about music. This idea is about both examining its past, lifting up old voices, and ensuring its survival. It’s what I enjoyed so much about Wednesday’s eclectic covers album. It’s why I was fascinated with Father John Misty’s singular retreat to the golden age of bandstand jazz. It’s why I connected to Beyoncé’s it’s-not-said-enough-how-weird-this-album-is Renaissance. And it’s what I loved about Alvvays’ Blue Rev, an album in thrall to little moments from music’s past and putting forth a bigger, singular idea about the sound of pop and rock music. I could annotate every meticulous detail of Blue Rev and still feel like there is more that I’m missing. The oblique, romantic, cinematic lyrics don’t make me wonder what Molly Rankin is feeling about something, or who she is talking about, or why. Instead, they reconnect to old ideas of mystery and obfuscation. When I am listening to these albums, I’m not just listening to music, I’m listening to more music.

I could argue that these things make Blue Rev gently in opposition to the mainstream, but I would hardly suggest that this is some kind of catalyst for radical change. But it also feels like a friend saying, “You know what I think you would like? A pop album that sounds amazing on vinyl with key changes, bridges, guitar solos, and a song that makes direct reference to Belinda Carlisle’s ‘Heaven Is a Place on Earth.’” That’s the true heart of criticism, casting about for a center in hopes to find yourself already there. You discover a song that is so who you are that you have no choice but to try and tell the world so that they can add you to their playlist.

1. Alvvays - Blue Rev

2. Jeff Parker - Mondays at the Enfield Tennis Academy

3. Special Interest - Endure

4. Father John Misty - Chloë and the Next 20th Century

5. Beyoncé - Renaissance

6. Jockstrap - I Love You Jennifer B

7. MJ Lenderman - Boat Songs

8. Soul Glo - Diaspora Problems

9. Grace Ives - Janky Star

10. Beth Orton - Weather Alive

11. Gilla Band - Most Normal

12. Big Thief - Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe You

13. Lucrecia Dalt - ¡Ay!

14. Makaya McCraven - In These Times

15. Yaya Bey - Remember Your North Star

16. Huerco S. - Plonk

17. Destroyer - Labyrinthitis

18. The Weeknd - Dawn FM

19. Panda Bear / Sonic Boom - Reset

20. Fievel is Glauque - Flaming Swords

21. Rosalía - MOTOMAMI

22. Two Shell - Icons EP

23. My Idea - CRY MFER

24. Sofie Birch - Holotropica

25. Anetloper - Pink Dolphins